The mahogany-paneled bar, tucked away in the shadowy depths of the exclusive country club, reeked of old money and older scotch. Sunlight was strictly forbidden in this inner sanctum, where the true power brokers gathered, far from the prying eyes of the lesser members (those whose net worth was a mere comma or two shy of the truly obscene). Here, deals were struck in hushed whispers, fortunes won and lost with a clink of ice in a crystal tumbler, and reputations forged in the fires of ruthless ambition. Today’s agenda? A private equity firm with a name that whispered of exclusivity and promised returns that could make Rockefeller himself weep with envy. That’s how getting into a private equity deal works, right? I like to imagine it is. The reality is the private markets have changed dramatically over the last decade or so.

The evolution of private markets, private equity specifically, has evolved significantly. Originally, if you were able to get into a deal or a fund, you’d make a commitment of capital. The fund managers would then go about placing that capital into deals and occasionally would make a capital call – demand for more of that capital you committed – to fund deals. This is often referred to as a draw-down fund. If you wanted in, this was the structure. It made managing the demand for cash a little difficult. The structure still exists in size today.

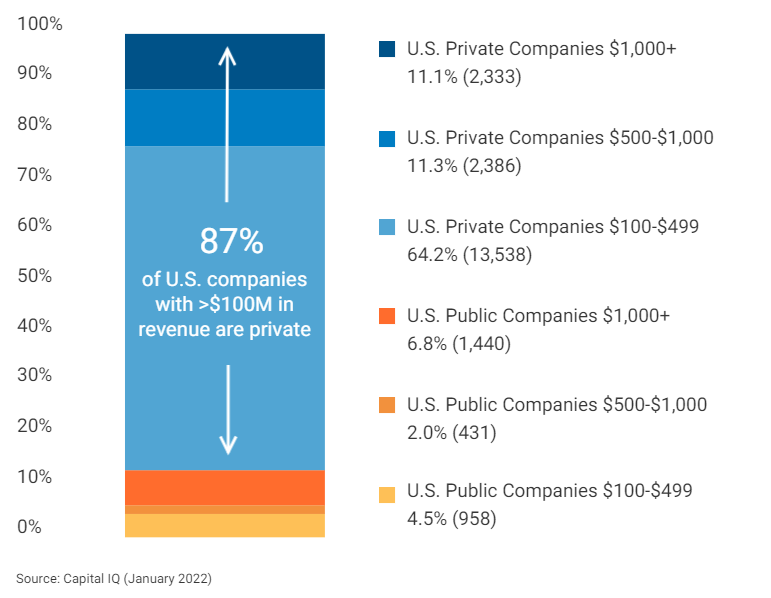

Companies are staying private for longer. At the beginning of 2000, there were 7,810 publicly traded companies in the US. At the end of 2020, there were only 4,814. There are 18,000 private companies in America with annual revenues over $100 million. There are only 2,800 public companies at that level. Companies just aren’t going public as fast, or at all. No longer is IPO the only path to exit. Dealing with the regulatory challenges required of public companies isn’t as appealing when the access and depth of private markets have grown considerably. Oh, and not to have to deal with the tick by tick stock price and quarterly reporting requirements probably helps too.

The appetite for access to private equity has never been greater. The country club deals have matured to more “normal” offerings. Sure, some of the best of the best funds require that you “be in the club,” but largely the access to private markets has reached the masses. Some funds require an investor to meet the qualified purchaser requirements of an investable net worth of at least $5M. Others an investor must only be an accredited investor, which means a $1M net worth or meet certain income thresholds or professional experience. A few are available to anyone.

Private equity firms aren’t dumb. Many have added a structure that doesn’t require the up-front capital commitment, managing capital calls, and having funds locked up for 7-10 years or more. They’ve created an evergreen structure that allows investors to make their full investment on day one and access funds periodically, often quarterly. That structure has been massively appealing to investors new to private markets.

Should every day investors begin allocating to private equity? The track record of returns is certainly appealing. You’ll hear promises of an “illiquidity premium” and “lower standard deviations,” relative to public equities. The illiquidity premium has some theoretical merit. Companies don’t have to worry about the quarterly reporting requirements and daily movement of their stock price like their public counterparts, so maybe they can take a longer term view when making decisions. But, the standard deviation argument is a bit of a ruse. Public companies obviously see what their stock is valued at any second of a trading day. Private companies, like our homes, don’t have that. Often, private funds will “mark” their investments on a monthly or quarterly basis. It’s essentially a valuation (guess) of what the companies are worth, but not necessarily what you could sell them for at that moment. Cliff Asness of AQR calls this “volatility laundering.” The reality is the market value of these companies is moving every bit as much as the public markets, but they get the benefit of that value not being visible 24/7/365.

There’s probably a behavioral benefit to being a private equity investor since you don’t visibly see your market values move as much and also can’t click a button and dump your position in seconds. It doesn’t mean they are actually less volatile.

The decision point as to whether it makes sense to allocate to private equity is no different than any other asset class. Time will tell if private equity will deliver what it’s promising. We are going to find out.

-R